A History Lesson with Chris Chaput

You ready to get started?

Sure. I have what’s called the gift of gab. Getting me to open up and talk about me, skateboarding, or products is not really hard. Getting me to shut up though… hahaha.

You started skating back in ’75, is that right?

No, actually a little bit before that. 1974. I was a teenager, thirteen. Born April 11th, 1961. At thirteen I started emulating some neighborhood kids, Tim and Jason, who had paper routes and skateboarded. They were surfer skaters.

Were you a surfer too?

No, here’s the problem. That’s the time in life when girls no longer have cooties, so this is the point where I’m like, “I need an angle here.” So I wanted to be a surf cat, only to find that my overly protective mother required seventeen years of junior lifeguard training before I could go to the beach on my own.

I started skating during the explosion of skateboarding. I got to be part of this growing industry and I got to be a part of a time when everybody skated everything. There were so many people doing different things that we naturally wanted to be part of it.

In 1975, I became the World Freestyle champion for boys aged twelve to fourteen. By the time another year rolls around, I’ve really stepped up my game. I briefly was a junior, then went pro and won the California Free Former World Skateboard Championships freestyle at Long Beach in 1976. That was featured in the Lords of Dogtown movie where I played the role of Russ Howell and recreated a lot of these scenes.

I practiced religiously across the street from my house. I was just obsessed. The sadness of not being able to be a surf cat and the desire to some day grow pubic hair and get laid was so strong. Geek no more.

Did it work? Did it help you get the ladies?

Well, the answer is eventually yeah. The first time I got laid I was on a trip. There was a girl hanging out with the skater guys, yada yada yada. But it was the heartbreak of not being able to be the surf cat, combined with flipping through the pages of Skateboarder Magazine, literally the Bible at the time, and thinking someday, somehow, if I got my picture in this magazine, if I was a part of this, that I would get laid for sure.

I practiced obsessively, slept with my skateboard because no woman would, you know, and I started developing equipment. At the time you would see a lot of boards with pointy noses, diamond tails, fish tails, stingers. Skateboarding was such a surf-influenced culture that all the skateboards looked like surfboards.

A skateboard to me was always a standing platform that was a lever to initiate lean steer. You’re never digging the rail into the ground, it’s not a snowboard, it’s not a surfboard, it’s not a thing where edges matter. The board is a steering platform for your feet, so the connection of your feet to your board was more important than how it looked.

Early on, making my own boards rather than what was commercially available was important. The Chapstick was notorious for being ugly, among other things, but I wanted something that worked first and foremost. Later on I was vindicated when almost every board started becoming more bulbous and square tailed and functional looking.

I also picked up a lot of information on how to win competitions. I would try to cherry pick everyone’s best trick and then be the guy who could put them all together. I would avoid the old school flip tricks, I called them fall tricks, and people wouldn’t really notice if they were missing. Later on that changed, thanks to Steve Rocco and Rodney Mullen, Mullen being the one who basically put the nail in the coffin and kicked everybody’s ass for years.

I heard about Bruce Logan’s headstand spinner, and thought, “Oh my god.” Among other things, you have griptape on your board while you’re doing a full rotation on your head. I had more hair on my head at the time, but I was like, “Shit, I gotta learn this.” Shortly after learning the headstand spinner, I’m at a competition in La Costa and I see Bruce Logan go out and do a headstand and do a quarter turn, push up into a handstand, and come back down to his board, and the announcer goes, “And there was Bruce Logan with the headstand spinner.”

“A QUARTER TURN?!? THAT’S THE HEADSTAND SPINNER?!?” I had it wrong, I had no idea. This is a testament to that childlike enthusiasm. I had read it in a magazine and assumed you had to go all the way around, so I taught myself something completely unnecessary that nobody else could do just to try to match Bruce Logan. That magazine was the Bible: I wanted to learn what these guys did, and so I learned a “headstand spinner”. I would have a little tuft of hair where the hair was growing back, I had long hair with a little putting green on top.

I went to Maryland for a little bit, but eventually I came back to California and had kind of retired from professional skating. In 1980 there was a competition at the Oasis skatepark. Steve Rocco was going to be there. We were thinking we would be one and two, and we get there and Rodney Mullen has come from Florida and we instantly recognized that we were vying for second place, he was that good.

The writing was on the wall, and the stage was set for a period of street skating and tricks that I had intentionally avoided up to that point. I also saw the grandiose venues shrinking. Kind of like how motocross was one time in fields and streams, then in a giant stadium, then inside a sports arena, and the next thing you know you just go and turn around, with a few whoops, super concentrated, with everyone running into each other. I don’t know how the motocrossers feel about it, but if you want the media coverage you dance the dance. I saw things going this direction and I didn’t like it.

Steve Rocco and Rodney, who would later combine forces at World Industries, are not single handedly responsible, and it’s not a bad thing, but what happened and what left a bad taste in my mouth was how small skating was getting. It became ledges and rails ad nauseum.

Also at this time, basically from 16 to 25, I’m increasing my alcohol and drug intake and I’m a full blown alcoholic by 22 or 23. Skating ended for the most part, college also ended due to drinking and stuff. But eventually I wanted to do the right thing and got sober in ’86. I’ve been completely alcohol and drug free since 1986.

So how did you get into downhill then?

Flash forward to about 1999. Waldo Autry, George Orton and some old school skaters are doing the X Games and they’re like, “Dude, you gotta come out and do this.” The X Games had an exhibition event for downhill skating, but it never actually picked up downhill. But IGSA and EDI, which were the race organizations of the time, definitely included downhill skateboarding and I did both of those.

The adrenaline I got after my first run just got me addicted to skateboarding all over again. And just like as a kid, I wanted to know who the players were, where the events were, what the equipment was.

It was also very different from freestyle, where you’re judged. I was drawn, naively, to the purity of racing. The first one to cross the finish line wins. Then enter politics, scandal, cheating, all sorts of other things. But I liked the process and I got addicted to racing. And with racing, products have a profound influence on your ability to perform, as does your talent. Every racer wants that silver bullet, they want that edge.

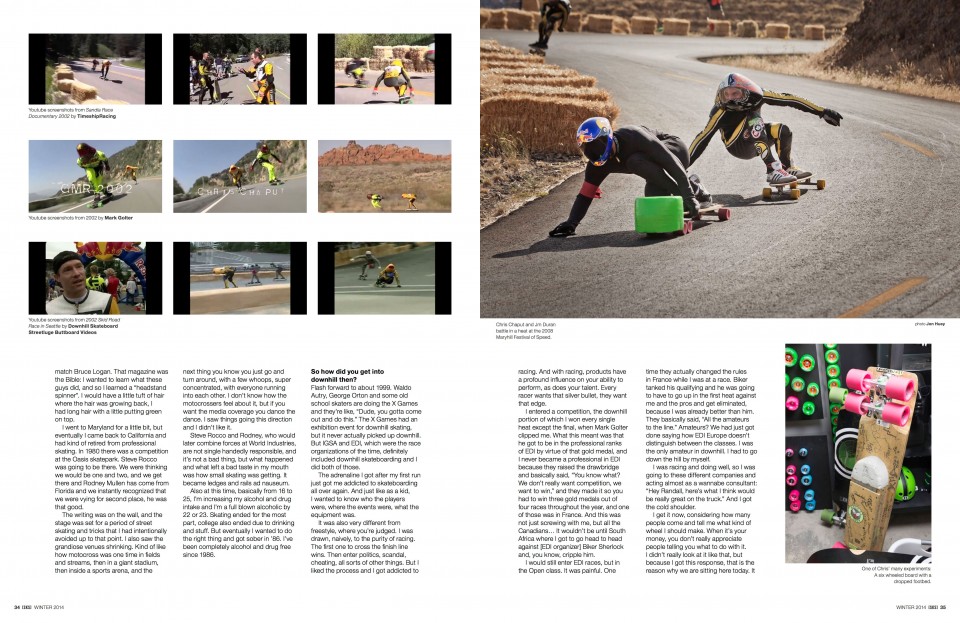

I entered a competition, the downhill portion of which I won every single heat except the final, when Mark Golter clipped me. What this meant was that he got to be in the professional ranks of EDI by virtue of that gold medal, and I never became a professional in EDI because they raised the drawbridge and basically said, “You know what? We don’t really want competition, we want to win,” and they made it so you had to win three gold medals out of four races throughout the year, and one of those was in France. And this was not just screwing with me, but all the Canadians… It wouldn’t be until South Africa where I got to go head to head against [EDI organizer] Biker Sherlock and, you know, cripple him.

I would still enter EDI races, but in the Open class. It was painful. One time they actually changed the rules in France while I was at a race. Biker tanked his qualifying and he was going to have to go up in the first heat against me and the pros and get eliminated, because I was already better than him. They basically said, “All the amateurs to the line.” Amateurs? We had just got done saying how EDI Europe doesn’t distinguish between the classes. I was the only amateur in downhill. I had to go down the hill by myself.

I was racing and doing well, so I was going to these different companies and acting almost as a wannabe consultant: “Hey Randall, here’s what I think would be really great on the truck.” And I got the cold shoulder.

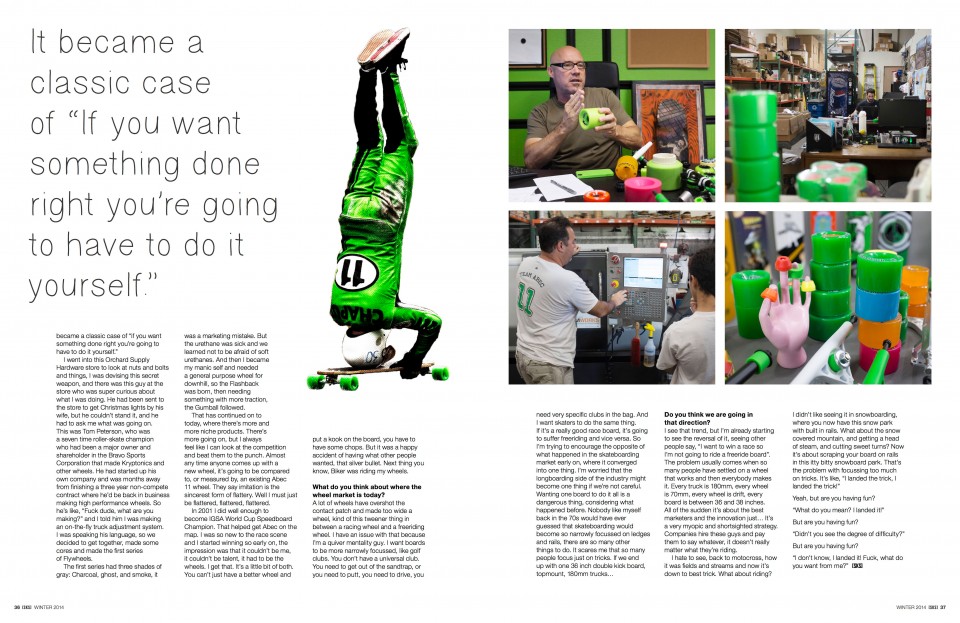

I get it now, considering how many people come and tell me what kind of wheel I should make. When it’s your money, you don’t really appreciate people telling you what to do with it. I didn’t really look at it like that, but because I got this response, that is the reason why we are sitting here today. It became a classic case of “if you want something done right you’re going to have to do it yourself.”

I went into this Orchard Supply Hardware store to look at nuts and bolts and things, I was devising this secret weapon, and there was this guy at the store who was super curious about what I was doing. He had been sent to the store to get Christmas lights by his wife, but he couldn’t stand it, and he had to ask me what was going on.

This was Tom Peterson, who was a seven time roller-skate champion who had been a major owner and shareholder in the Bravo Sports Corporation that made Kryptonics and other wheels. He had started up his own company and was months away from finishing a three year non-compete contract where he’d be back in business making high performance wheels. So he’s like, “Fuck dude, what are you making?” and I told him I was making an on-the-fly truck adjustment system. I was speaking his language, so we decided to get together, made some cores and made the first series of Flywheels.

The first series had three shades of gray: Charcoal, ghost, and smoke, it was a marketing mistake. But the urethane was sick and we learned not to be afraid of soft urethanes. And then I became my manic self and needed a general purpose wheel for downhill, so the Flashback was born, then needing something with more traction, the Gumball followed.

That has continued on to today, where there’s more and more niche products. There’s more going on, but I always feel like I can look at the competition and beat them to the punch. Almost any time anyone comes up with a new wheel, it’s going to be compared to or measured by an existing Abec 11 wheel. They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Well I must just be flattered, flattered, flattered.

In 2001 I did well enough to become IGSA World Cup Speedboard Champion. That helped get Abec on the map. I was so new to the race scene and I started winning so early on, the impression was that it couldn’t be me, it couldn’t be talent, it’s had to be the wheels. I get that. It’s a little bit of both. You can’t just have a better wheel and put a kook on the board, you have to have some chops. But it was a happy accident of having what other people wanted, that silver bullet. Next thing you know, Biker was riding my wheels.

What do you think about where the wheel market is today?

A lot of wheels have overshot the contact patch and made too wide a wheel, kind of this tweener thing in between a racing wheel and a freeriding wheel. I have an issue with that because I’m a quiver mentality guy. I want boards to be more narrowly focussed, like golf clubs. You don’t have a universal club. You need to get out of the sandtrap, or you need to putt, you need to drive, you need very specific clubs in the bag. And I want skaters to do the same thing.

If it’s a really good race board, it’s going to suffer freeriding and vice versa. So I’m trying to encourage the opposite of what happened in the skateboarding market early on, where it converged into one thing. I’m worried that the longboarding side of the industry might become one thing if we’re not careful.

Wanting one board to do it all is a dangerous thing, considering what happened before. Nobody like myself back in the 70s would have ever guessed that skateboarding would become so narrowly focussed on ledges and rails, there are so many other things to do. It scares me that so many people focus just on tricks. If we end up with one 36 inch double kick board, topmount, 180mm trucks…

Do you think we are going in that direction?

I see that trend, but I’m already starting to see the reversal of it, seeing other people say, “I want to win a race so I’m not going ride a freeride board”. The problem usually comes when so many people have settled on a wheel that works and then everybody makes it. Every truck is 180mm, every wheel is 70mm, every wheel is drift, every board is between 36 and 38 inches. All of the sudden it’s about the best marketers and the innovation just… It’s a very myopic and shortsighted strategy. Companies hire these guys and pay them to say whatever, it doesn’t really matter what they’re riding.

I hate to see, back to motocross, how it was fields and streams and now it’s down to best trick. What about riding? I didn’t like seeing it in snowboarding, where you now have this snow park with built in rails. What about the snow covered mountain, and getting a head of steam, and cutting sweet turns? Now it’s about scraping your board on rails in this itty bitty snowboard park. That’s the problem with focussing too much on tricks. It’s like, “I landed the trick, I landed the trick!”

Yeah, but are you having fun?

“What do you mean? I landed it!”

But are you having fun?

“Didn’t you see the degree of difficulty?”

But are you having fun?

“I don’t know, I landed it! Fuck, what do you want from me?”